In this issue of The Ramspondents

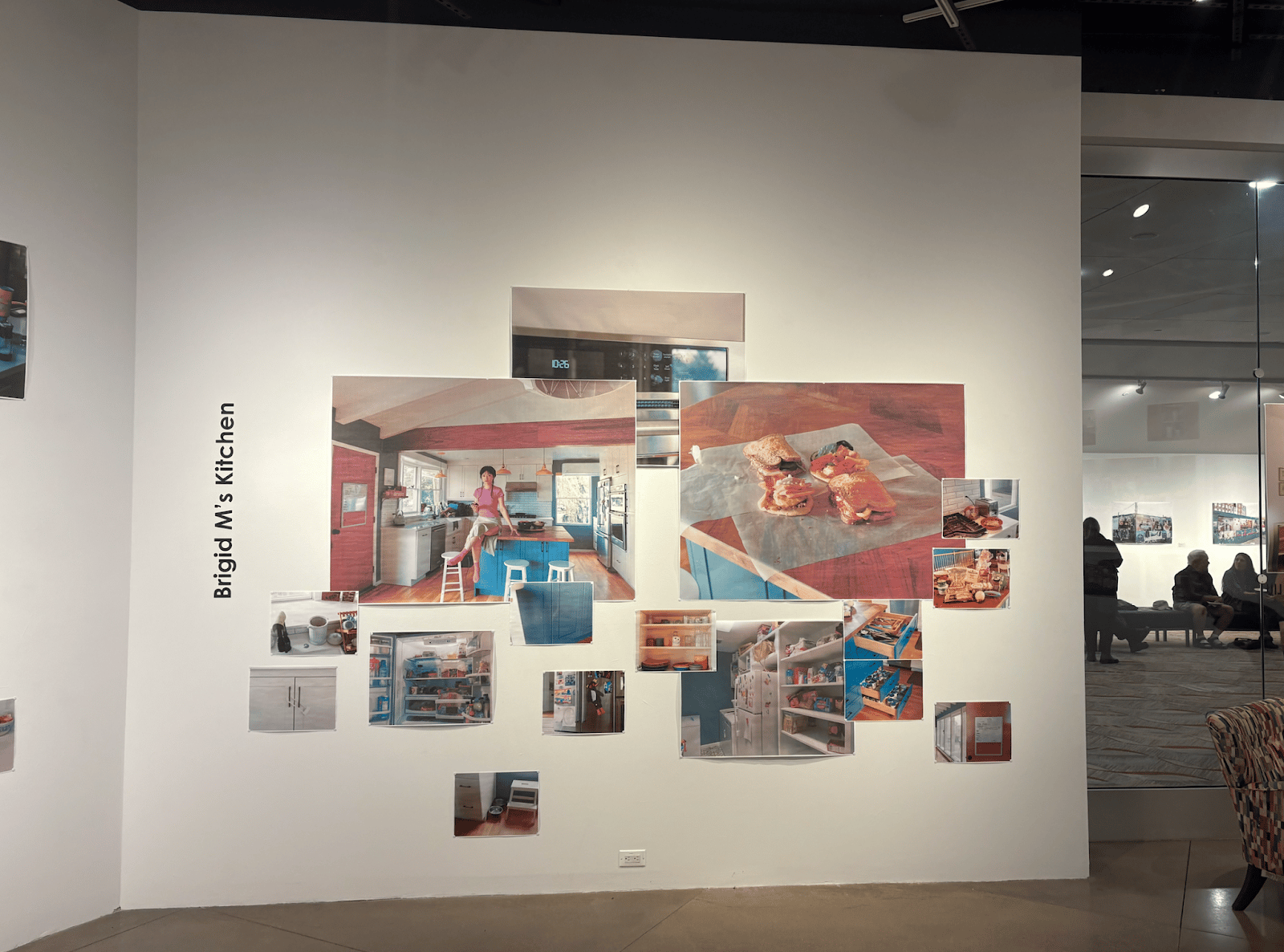

The Conch Girl Project is showing now at the Lincoln Center art gallery

By Maximus Vogt

The Ramspondents

For five hours, Brooklyn-based artist Sidian Liu stood alone in a stranger's kitchen in Fort Collins with a medium format camera in hand, preparing a meal for someone she had never met. Careful choreography and care forms the heart of The Conch Girl Project, an ongoing photographic investigation into displacement, domesticity, and the radical vulnerability required to forge a sense of home in unfamiliar terrain.

Origins: Stealing Light

Liu's trajectory into strangers' kitchens began with a sense of yearning for warmth and belonging that arose from isolation. When she arrived in New York from China in 2021, the city was still gripped by pandemic lockdown. Her first American Christmas met her with complete boredom as her new friends fled to family homes. She took this opportunity to wander through the busy New York streets with a camera.

"I took a lot of photos of people's windows because in New York City, people put a lot of effort in decorating the interior space close to the window," Liu said. "You can walk on the street and see Christmas trees, lights, festive decorations. It seemed like an effort of arranging your home to look cozy and in comparison my window back then was super empty."

This photographic curiosity evolved into Stealing Light (2022), an installation that surrounded viewers in projected images of the windows she captured. In the centerpiece video, Liu lies within a mosquito net (an object necessary from her childhood in China, now obsolete in New York) as these collected domestic scenes wash over the translucent fabric. The net becomes a porous barrier between external realization and bodily reality, deflecting her potential intrusion while admitting warmth. Liu describes the work as an attempt to steal comfort from carefully curated domestic scenes, to inhabit the sense of home radiating from other people's carefully composed interiors.

As winter hibernation ended and spring was imminent, observation no longer sufficed. "I realized what I really wanted was actually behind those windows," Liu explains. She began to ask herself "Is it possible to literally get into stranger’s homes? What am I willing to do to realize that?"

The kitchen is the answer

The answer materialized through cooking, an activity Liu identifies as the phenomenological center of home-making and an act of care that could secure an invitation into a home.

"The kitchen is the core space of a home. It is the space where you have conversations, where you take care of yourself first and then you can also take care of others," she said.

Her relationship to cooking is complex, shaped by gendered labor expectations in her childhood home where she assumed family cooking responsibilities by middle school. Liu was careful to note that this expectation was not representative of broader Chinese culture, but existed as a stark moment in her own girlhood. She recognizes the paradox that comes with the knowledge of cooking as an act that also generates autonomy. "Wherever I end up, I can at least fix myself a meal."

The project's title references a Chinese folk tale: a fisherman discovers a conch shell that transforms daily into a goddess who cleans his home and prepares meals. Liu repurposes this myth, positioning herself as both goddess and critic, performing domestic labor not as invisible labor but as an apparent power play. In doing so, she reframes cooking as "radical care,” a term with legacies in feminism and ensuing social art practice, namely the divisions of labor investigated in the work of artists like Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro.

The Conch Girl Project enters this artistic dialogue and transforms domestic skill into a mode of social negotiation. Liu wheat-pastes open calls onto ivy-green construction boards that constantly proliferate across New York's streetscape. She engages with an element of chance here as these boards are typically ephemeral places for quick guerilla marketing. This choice brings the work to the pedestrian, to the chance encounters that echo the vulnerability of meeting strangers.

Strangers scan a QR code on the open call sheet, sign up; Liu arrives and a transaction of trust unfolds.

The process is meticulously crafted to preserve Liu's autonomy while manufacturing intimacy. "The way I do it is I ask for the least amount of face-to-face contact," she explains. "Usually the kitchen owners would either leave the household completely and leave me alone there, or they stay in another room, but leave me totally alone in the kitchen area."

This spatial separation is Liu’s singular cardinal rule. When one group of participants attempted to observe her work, Liu physically confined them to a bedroom, later photographing the accumulation of shoes outside their door as evidence of the awkward surveillance they enacted.

Liu arrives with only her deliberately large medium-format camera, seeking to negotiate power in her choice of technology.

"I chose it because it shows that I have enough time to maneuver it and enough space to move it around," she says. "It's basically an act of claiming a certain level of agency."

She brings no groceries, cooking exclusively from the kitchen's existing inventory. This constraint prevents performative restocking and ensures the kitchen's authentic state, creating a breathing artifact that depicts rhythms of consumption, a home chef’s aspirations and neglect.

The resulting photographs allow the viewer to relish in her archaeological discovery that lies behind private cupboards and reinvigorates human curiosity in the banal. Liu's self-portraits within these spaces position her as a temporary inhabitant, her countenance calm and posture dignified, reclaiming cooking from its relegation to gendered domestic labor. Other images catalog the kitchen's particularities: the elegantly curated interiors of a small New York City kitchen to the sparse inventory of a dormitory kitchenette, the arrangement of objects that betray class, culture, and care.

Publications and illusions of permanence

After each visit, Liu requests written responses from kitchen owners. These range from terse emails to elaborate floor plans drawn by architect participants, from creative fiction to brief acknowledgments of shared awkwardness. In New York, she wheat-pastes the resulting photographs and correspondence onto the same construction boards that initially solicited participation, creating a feedback loop of presentation and invitation. The large-scale street publications mimic advertising's visual currencies: images, slogans ("May I use your kitchen?"), QR codes while selling nothing, instead proposing an economy of attention and exchange.

This guerrilla exhibition strategy acknowledges its own precarity. Construction sites transform constantly; boards are dismantled, replaced, obscured. The work accepts temporal vulnerability as a necessary component, existing only in the margins of material development before an inevitable demise. Lis said this practice cannot translate to Fort Collins, where scaffolding is rare and attention moves at automotive speeds rather than pedestrian pace.

Despite complete impermanence in a tangible realm, Liu’s domestic adventures are forensically documented online where each endeavor is titled with the resident’s name and the meal she prepared. On each of these listings she includes her photos, often with her self-portrait in the fore and lists the "ingredients" in step-by-step format that culminated in a complete visit. These ingredients are written as diaristic descriptions of the kitchen encounters with detailed notes of the brief interactions with the residents, leading the reader to postulations in psychological examination. Through this documentation, the project begins to model social experimentation, as if to measure metrics of affect in trust and belonging that serve as evidence to test a hypothesis founded in contemplations of connection.

Fort Collins: abundance and completion

Liu's expansion to Fort Collins came through the 2024 Denis Roussel Fellowship from the Center for Fine Art Photography, which closed permanently this January. Over one week in September 2024, she cooked in six local kitchens, encountering a scale of domestic space foreign to her New York experience.

"Every house is so big, every kitchen is at least twice as large," Liu said. "There's definitely abundance of stuff in the pantry or in the cabinet or in the fridge, and the items in the fridge would be in big packs and that's something that New York City doesn't really need."

Liu recalled that abundance generated its own challenges: more decisions about what to cook, more spatial possibilities for photography, more time spent negotiating choice itself. This new frontier allows for continued avenues of autonomy, more space that can be conquered and greater possibility for the suburbanite’s “American dream’ to be critically examined. Yet, Liu is careful not to colonize, despite confident self-portraiture, the dedication to documentation and that careful separation in an investigative process yield her own product with only a temporary imprint on the space.

The Fort Collins iteration, now exhibited at the Lincoln Center for Creativity, marks a potential conclusion. After four and a half years in New York, Liu suggests the project's originating urgency as the hunger for belonging and the need to manufacture home has now diminished. The artistic curiosity and experimentative process have resulted in a formulation of interpersonal exchange as a vital practice, something accessible in theory but daunting in a post-isolation society. Her work does not ask the viewer to intrude on spaces with voyeuristic desires but that recognize our neighbors through possibilities of trust. Liu’s work then challenges the viewer to explore opportunities for connection that surround them.

“I think that project it really opens my mind about how kind strangers can be to each other and I think thats in the fact that my ideas can be realized again and again and so many times,” Liu said. “I feel like I can at least be received in this place and be helped and supported.”

The Conch Girl Project is showing at the Lincoln Center’s art gallery through Dec 19, 2025.

Maximus Vogt is an art history major and journalism minor at CSU, active in fine art happenings on campus. He is interested in the intersection of art, community and news.

What’s happening this holiday season in Fort Collins

Calvin Masten

The Ramspondents

With Thanksgiving in the rearview and Fort Collins receiving a light dusting of snow, the holidays are in full swing. Whether it be photos with Santa or a holiday marketplace, here’s everything happening this month in Fort Collins to get you in the festive mood.

Starting on Dec. 1st - Photos with Santa

Get your or your pet's photo taken with Kris Kringle himself at the Foothills Mall. Santa will be periodically taking photos with visitors in the shopping center from 2-7 p.m., and with their furry friends on the 8th and 15th of the month from 4-7 p.m. Walk-ups for both photo shoots are welcome, but reservations can also be made online.

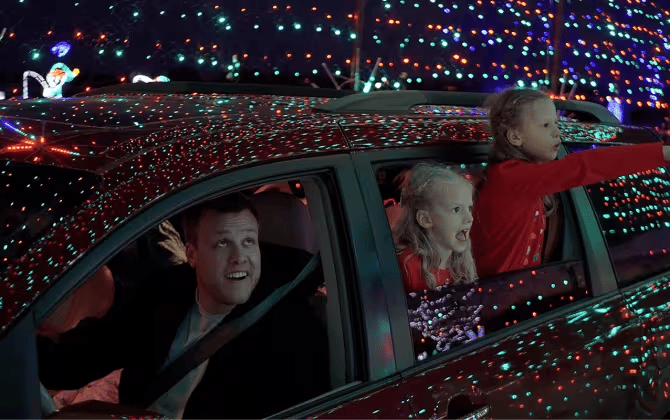

Nov. 28 to Jan. 1 - NoCo Winter Wonderland

All photos taken from the Visit Fort Collins website.

The Colorado Youth Outdoors' annual drive-thru light show is back in Fort Collins, and for $25 a vehicle, you and your family can enjoy a night of holiday lights without leaving the warmth of your car. Located at 4927 E. County Road 36, the light show occurs every Sunday, Thursday, Friday, and Saturday of the month from 5:15-8:15 pm.

Dec. 6 - Visit Santa's Reindeer at Bath Garden Center

For $5, Fort Collins residents can visit the Bath Garden Center and Nursery to meet Santa’s trusty reindeer, sip hot cocoa, write letters to Santa, make holiday crafts, shop for holiday gifts, and more. The event runs from 8:30 a.m. to noon and is located at 2000 E. Prospect Road.

Dec. 12 - Holiday Celebration at Jessup Farm

Explore a variety of unique holiday gifts, sample fun treats, take photos with Santa, and take part in a holiday scavenger hunt at Jessup Farm Artisan Village on Dec. 12. The event is free to all and will run from 4-8 p.m.

Dec. 15 - Ginger and Baker Holiday Market

Ginger and Baker’s Teaching Kitchen will be hosting a market from 9 a.m. - 3 p.m. on Dec. 15. Admission is free for all to come and discover holiday goods from a large variety of local makers, like handmade gifts, plants, and goodies.

Dec. 19-20 - A Drag Christmas Spectacular

A Drag Christmas Spectacular is back for its third year on Dec. 19-20 at 1815 Yorktown Ave. The show is a retelling of the Christmas story, full of glitter, gospel, heart, and a dedication to its Trans, Nonbinary, and BIPOC artists. Ticket prices vary, and the show happens both days from 7-10 p.m.

Dec. 21 - Breckenridge Brewing Holiday Market

From noon to 5 p.m., residents can come to the Breckenridge Brewery to enjoy a variety of local vendors and artists.

Calvin Masten is a third-year Journalism and Media Communication major and Sociology minor at Colorado State University. His fondness for interpersonal stories and human connections drives his enjoyment of writing, editing, and filming.